By Dr. Terry Macaluso, Head of School

Memory is puzzling. Case in point, ask my siblings what they remember about the family trip to Disneyland in 1963, when we all traveled to Uncle Mike’s house for Thanksgiving. The holiday was on the 24th; we were scheduled to go to Disneyland on the 23rd, and to fly home on the 25th. But Disneyland was closed because of the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy; Disneyland never happened.

I am the oldest—eleven years old. I remember being afraid because of the assassination. There was so much speculation about what it might mean. My sister, three years younger, remembers not liking the turkey dressing or the olives. In my sister’s experience all olives were black; whose idea was this green impersonator? My brother, six years younger, remembers being sad because we couldn’t go to Disneyland; the Mickey Mouse ears had no impact on his despair. Three siblings—all in the same place at the same time. Each with a primary recollection utterly unrelated to the others.

BUT WHAT OF REFLECTION?

As I reflect now, on that long-ago time, the sixty years between then and now have taught me myriad lessons about what that historical day might have meant. Recollection is the subjective relationship one has with a specific moment; reflection is composed of recollections that have been eroded by the passing of time and chiseled by the unstoppable movement toward whatever is next.

Similarly, those of us who were involved with Eastside Prep in its earliest incarnation disagree on details. We have different primary recollections. Was the population of the first class of sixth and seventh graders seventeen or sixteen? How many square feet were there on the lower level of the single building that was the original Middle School? Why did we add grade five in the same year we had our first graduating class? How much time was available to raise $5MM from the community to receive the $5MM match that had been offered? Were the trustees ever asked to pass the hat to balance the budget at the end of the fiscal year?

Similarly, those of us who were involved with Eastside Prep in its earliest incarnation disagree on details. We have different primary recollections. Was the population of the first class of sixth and seventh graders seventeen or sixteen? How many square feet were there on the lower level of the single building that was the original Middle School? Why did we add grade five in the same year we had our first graduating class? How much time was available to raise $5MM from the community to receive the $5MM match that had been offered? Were the trustees ever asked to pass the hat to balance the budget at the end of the fiscal year?

There are hundreds more pieces of experience that stand out as discreet instances. The post office box was never filled with applications. Maybe there was one. Sometimes as many as two. I went to the post office every day, wincing as I turned the key in the lock—fearing that there would be nothing there. Most of the time, my fear was legitimate.

By the time we had hired enough teachers and staff to serve a student body of forty-five, most of us had become believers.

We had to hire teachers. To teach—What? Whom? Where? Why? We had a dozen philosophical conceptions of the ideal curriculum, with no real idea whether the people we hired would be able to do the thing we wanted them to do. And we didn’t know whether the thing we wanted them to do was the thing we should want them to do. There are endless stories about used furniture. For example, sheets of acrylic shower-wall sheeting were transformed into white boards. We had four classrooms completely covered with the stuff so people could write on every surface in the room. Unfortunately, erasing words and images proved to be too great a challenge. Ultimately, we would buy one white board for the same price that we paid to make every room a “walk-in” white board.

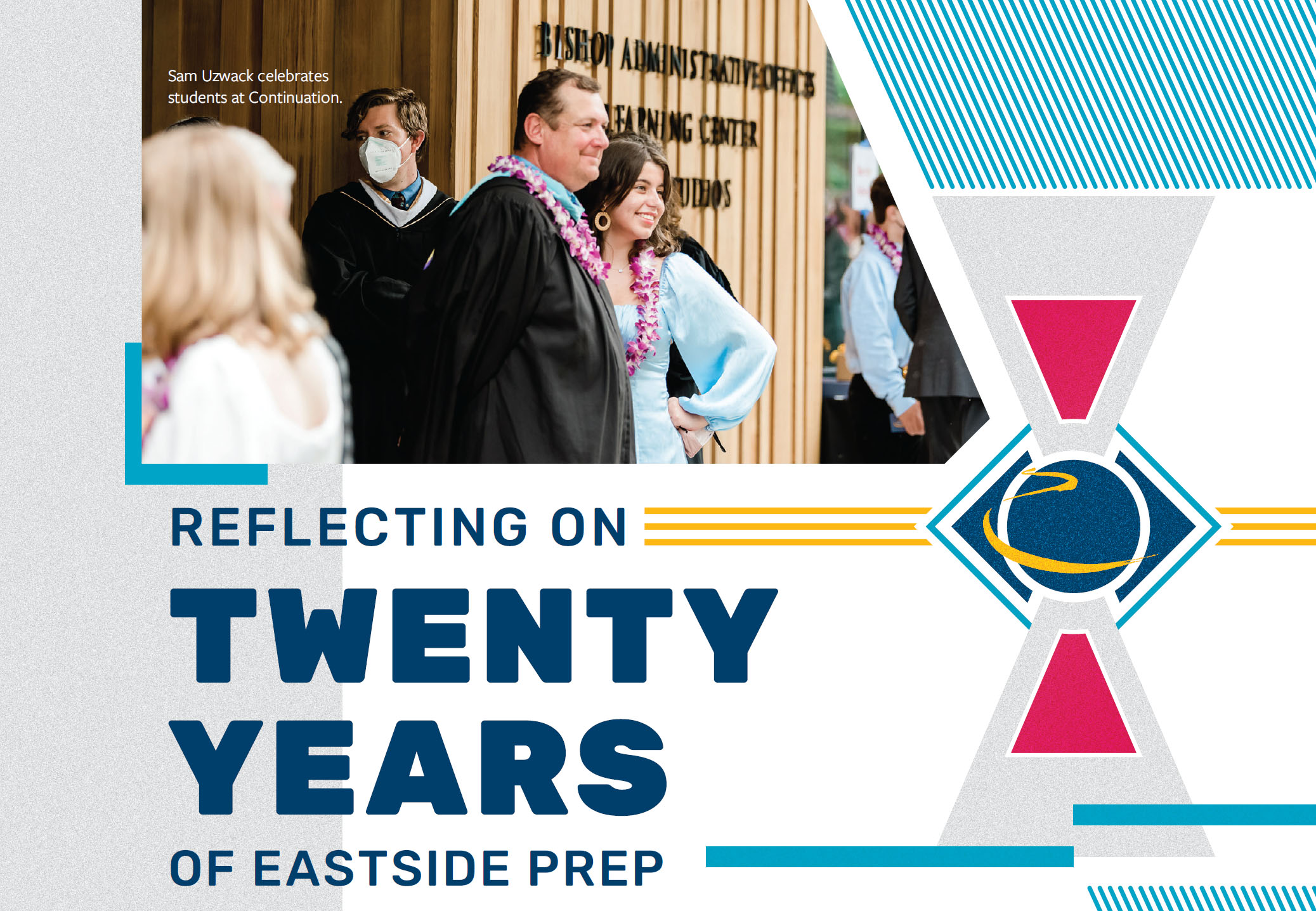

There are hundreds of stories like this that compose the content for the reflections it is now possible to conjure. What it takes to continue forward with a project that has no reason to expect to be successful is idealism, vision, and tenacity. Our first graduating class had eleven students in it. Our second had four. What kind of faith does it take to look at numbers like that and continue behaving as though we were going to thrive? What is the personal cost of tying one’s professional future to an organization that—on the face of it—has no reason to imagine that it would survive, much less thrive. This is exactly the place where reflection converts all those isolated memories into a story.

I was motivated by an unconditional confidence in the people with whom I was working. Every year we added interesting and interested educators.

By the time we had hired enough teachers and staff to serve a student body of forty-five, most of us had become believers. What I’ve wondered about for twenty years is,“Why?” What fueled the positive energy? What made us feel as though failure was not an option? How could we possibly answer this question, “How are you going to maintain the culture in a school that has tripled in size within three years?” That would be the question asked, repeatedly, throughout the life of the school. When enrollment reached 200, the twenty employees gathered for a champagne toast. Some families and students feared that we were becoming a gigantic school in which the personal nature of our relationships would surely suffer.

I was motivated by an unconditional confidence in the people with whom I was working. Every year we added interesting and interested educators. I stopped wondering whether we would be successful just by watching them work. I stopped visiting the post office every day. And when we had a real address, we closed the post office box entirely. The project began to feel real when I knew it had to be successful—because of the values it stood for.

I was motivated by an unconditional confidence in the people with whom I was working. Every year we added interesting and interested educators. I stopped wondering whether we would be successful just by watching them work. I stopped visiting the post office every day. And when we had a real address, we closed the post office box entirely. The project began to feel real when I knew it had to be successful—because of the values it stood for.

One of the drivers for me in the design of the school and in thinking about the kinds of teachers we would want to hire was based on previous experiences I’d had in schools as an educational leader. The political split between teachers and the people who lead them is anathema to successful education. Whatever the causes of such animosity, the energy required to fight it detracts from the positive work of creating experiences for children and adolescents who are entirely dependent upon all of us—parents, staff, and teachers—to do the things we must do within the roles we inhabit.

From its earliest inception, EPS was to be a place in which adults would work as collaborative partners—trusting one another that whatever each was assigned to do would be done—and done well. We would all assume positive intention on the part of our colleagues. Decisions would be made with the best interest of the whole. Without that trust, nothing good could have happened.

It takes time to learn to trust. It takes the repetition of actions to provide the evidence that trust is well-placed.

Here the reflection begins to take substantive shape. The more we emphasized the power of trust, the stronger our connections became. Staff, teachers, and parents formed partnerships to build a web strong enough to hold every student in our charge.

We continued to grow. At 400, the worries about the loss of culture were audible everywhere. The culture changed—as all cultures do all the time—but we did not lose the sense of communal trust that had prevented EPS from becoming just like many other schools…divided, in conflict, working at cross purposes, failing to maintain reciprocal trust between teachers and school leadership.

AND THEN IT WAS MARCH 2, 2020

A quarter of our faculty and staff were hired between March 2020 and June 2022. Over 200 of our current students were admitted within that same time frame. We didn’t see much of each other during that long uncertain time, but we’re beginning to get to know each other again.

For the better part of two years, we did whatever was necessary to keep learning alive. But what we couldn’t compensate for was the missing months of social and emotional development of individual students. We knew that loss was serious while we were in it; what we could not know until there was enough distance between then and now, was what it would take to recover.

As I reflect on the immediate past and remember some of the stories that emerged from the creation of EPS, I find one immutable truth. We can write messages, we can plan, we can strategize, we can promise, and we can imagine—but unless we’re doing that in community we have nothing to show for it. We didn’t lose our culture—not even two years of pandemic could cause that—so much as we have forgotten some of its components. It takes time to learn to trust. It takes the repetition of actions to provide the evidence that trust is well-placed. We have begun to write the EPS story again—and this is not the last time we’ll “restart” ourselves.

The value of reflection is that it shows us, again, things we have known and cherished. It reminds us of commitments made long ago and of the challenges that, in retrospect, were not nearly as challenging as we believed them to be at the time. It allows us to review where we have been and how we arrived at the place where we are. Finally, reflection invites us to make meaning of a series of events and decisions that, taken altogether, provide a glimpse of what is still possible.