WE’RE NOT COMING BACK;

WE’RE MOVING FORWARD.WE’RE NOT GETTING BACK TO NORMAL;

WE’RE INVENTING A NEW ONE.

By Dr. Terry Macaluso, Head of School

IN PURSUIT OF “WHAT’S NEXT,” I DID A LITTLE BIT OF research to learn what I could about the origins and aftermath of the 1918 flu epidemic. One hundred years ago, fifty million people were lost to the flu, which, when added to the number of soldiers lost in World War 1, left precious few men available to regenerate the economy.

Like many others, I became curious about the 1918 flu epidemic while navigating the 2020 version. We’re clearly in better shape today, but the mortality statistics from 100 years ago are not all that much worse than they are today. Statistics show that 675,000 Americans died in the 1918 epidemic. As of June 2021, the United States has lost more than 600,000 citizens… and counting.1

I was curious, as well, about how the respective pandemics began. We’re all aware of the controversy around the origins of COVID-19. In 1918, the first indication of the flu in the United States is thought to have been in Alaska (which didn’t officially become a state until 1959) in a small village called Brevig Mission.

Today, fewer than 400 people live in Brevig Mission, but in the fall of 1918, around 80 adults lived there, mostly Inuit Natives. While different narratives exist as to how the 1918 virus came to reach the small village—whether by traders from a nearby city who traveled via dog-pulled sleds or even by a local mail delivery person—its impact on the village’s population is well documented. During the five-day period from November 15-20, 1918, the 1918 pandemic claimed the lives of 72 of the villages’ 80 adult inhabitants. 2

Neither in 1918 nor in 2020 were/are we confident that we know, absolutely, what started the virus. While that is, of course, a matter of urgency for scientists, the aftermaths in each of the epidemics have been profound influencers of economic and social transformation.

The researchers estimate that in the typical country, the pandemic reduced real per capita GDP by 6 percent and private consumption by 8 percent, declines comparable to those seen in the Great Recession of 2008–2009. In the United States, the flu’s toll was much lower: a 1.5 percent decline in GDP and a 2.1 percent drop in consumption.

The decline in economic activity combined with elevated inflation resulted in large declines in the real returns on stocks and short-term government bonds. For example, countries experiencing the average death rate of 2 percent saw real stock returns drop by 26 percentage points. The estimated drop in the United States was much smaller, 7 percentage points. (https://www.nber.org/digest/may20/social-and-economic-impacts-1918-influenza-epidemic)

The economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have not been fully realized, nor do we have definitive information on precisely what that impact might be. We’ve certainly seen dramatic signs of social change, however, and it will be interesting to see just how profound change will be.

One recent headline on a popular news site reads: “Why American Workers Don’t Want to Go Back to Normal.” There’s a social AND economic impact—all rolled into one. I’ve heard the same thing from faculty, staff, and students. So, what IS the new normal, or should we expect to see many ew normals?

Survey data throughout the pandemic allowed us to follow our families as time passed and the real impact of isolation was felt. For some students, the lack of social interaction was painful; for others, it was a relief from the anxiety they experience at school every day. For some, distraction was a major concern; for others, concentration was improved.

OF ALL THE LESSONS COVID-19 TAUGHT US, PERHAPS THE SINGLE MOST SIGNIFICANT LESSON IS THAT WE ARE, NO DOUBT ABOUT IT, SOCIAL ANIMALS.

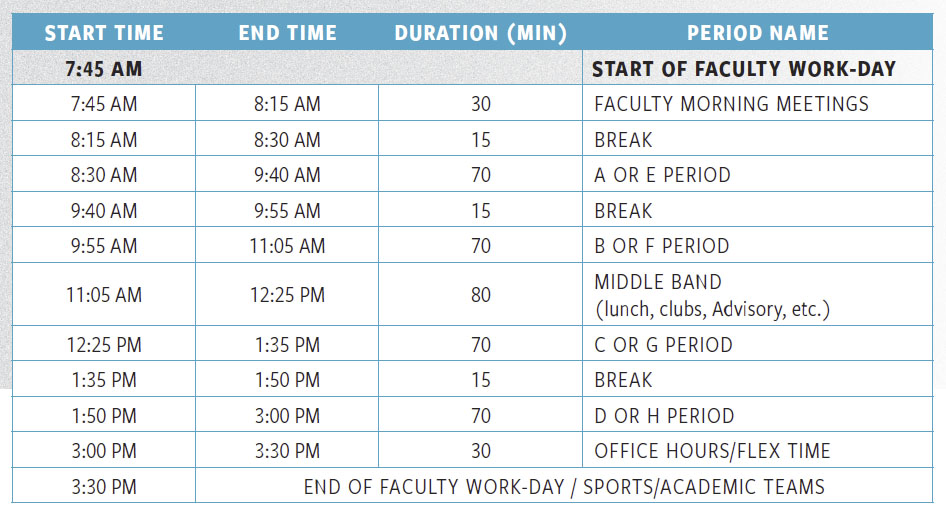

DAILY SCHEDULE FOR 2021-2022

Not unlike the typical school experience preceding COVID-19, people have different reactions to what they experience. That will most certainly continue, but what might we have learned from the “COVID-19 months” that can inform our practice going forward?

- The school day should start later—the benefit of additional sleep had an impact on everyone.

- The amount of homework we assign students needs to be carefully reviewed. During our separation, it was clear that students were spending more time on assignments than faculty expected. Should we include with each assignment a general range of time to be invested on each assignment?

- Students and faculty need more free time during the day to reduce the feeling of “frenzy” that is created by the short time provided between classes.

- Students should be able to participate in after-school activities and still be able to get home at a reasonable time. Overall, the day should be a little bit shorter.

All this information fed our collaboration about the new schedule, implemented in fall, 2021 (shown above).

The more difficult set of possibilities involves the school’s capacity to deliver content via Microsoft Teams. We were veryfortunate during the period of quarantine in March 2020 through March 2021, because we were able to provide remote instruction. Teachers liked it and students liked it—for the most part—at least for the first three months. Feelings about remote instruction began to sour as the weeks and months came and went until, finally, we were able to bring

most students back to campus in March, 2021. This is where we learned what really doesn’t work. What REALLY doesn’t work is hybrid instruction. Teaching to two audiences in two different places is a little bit like being in a discussion while you’re on your cell phone—and the discussion you’re having does not involve the person on the other end of the line.

IDEAS ABOUT SLEEP, COMMUTING, MENTAL AS WELL AS PHYSICAL REST—ALL OF THOSE ARE SOMEHOW DIFFERENT—BECAUSE WE’VE EXPERIENCED A WAY OF BEING THAT WE HADN’T EXPERIENCED BEFORE.

Since so much of an Eastside Prep education involves DOING THINGS as opposed to WRITING THINGS DOWN, we are choosing an educational model that prioritizes real-time, shared experiences. In situations in which a student must, for health or other documented reasons, be remote, we will allow the student to observe the class, but it will only be a broadcast—not direct instruction.

Of all the lessons COVID-19 taught us, perhaps the single most significant lesson is that we are, no doubt about it, social animals. We missed having breakfast and lunch together, running in to one another while passing from class to class, performances, sports, science labs, and Maker Spaces.

It’s important to understand that faculty and staff worked tirelessly throughout the remote and hybrid phases of instruction from March 2, 2020 until June 14, 2021. The EPS education never lapsed, but minds and attitudes have been impacted after spending fifteen months apart. Ideas about sleep, commuting, mental as well as physical rest—all of those are somehow different—because we’ve experienced a way of being that we hadn’t experienced before.

Coming soon…watch this space.