By Jonathan Briggs, Director of Strategy, Technology and Innovation

COLLECTIVE DELUSIONS FASCINATE ME. THEY ARE A complex interaction between systems and people and if they are believed strongly enough, they are conjured into existence. They are everywhere—some of them are helpful to society, others do harm, some shift power structures, others solidify existing ones.

The first example that comes to mind is some sort of cult. Indeed, the definition of a cult, “a misplaced or excessive admiration for a particular person or thing,” fits the definition well. We see delusion in the traditional religious cult context, and in less extreme forms in the Mac vs. PC, Ford vs. Chevy, Portland vs. Seattle, Coke vs. Pepsi arenas, where the allegiance to one “team” over another is stronger than the actual differences between teams (and yes, I have a side in each of the battles listed: clearly it is PC, Chevy, Seattle, and Coke). In each of these examples, people understand that others feel strongly in one direction or the other. Beyond these—often false—dichotomies, there are other delusions that are so widely held that we don’t realize that we are deluding ourselves collectively.

Money, the thing that can be traded for all manner of things like houses, cars, and food is perhaps our most impressive collective delusion. When you come right down to it, it is paper; nice paper, but paper nonetheless. Today, what money is, is even more abstract. When I get paid, a couple of banks agree to do some arithmetic using some electronic signals; nothing physical is exchanged. At the store I tap my phone against a kiosk and leave with a bag of real stuff. In this sense, money is both a real thing and a collective delusion. We embrace it because it’s useful and simplifies transactions for humans.

There are collective delusions that are pervasive and problematic. As an illustration, go to gapminder.org to take a five-minute test on your general knowledge of global health. It consists of thirteen multiple-choice questions, developed by the amazing folks at Gapminder to test people’s general knowledge of global health.

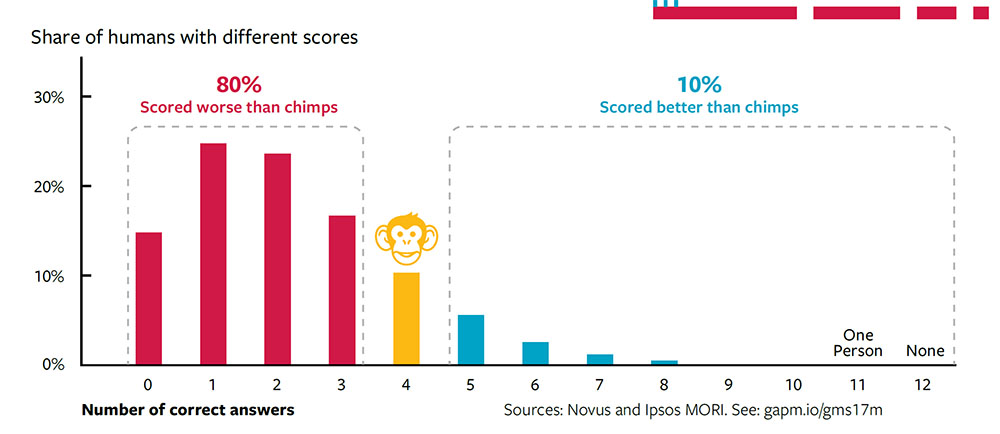

If you picked an answer without reading the questions you would, on average, score a 4.33 out of 13. The folks at Gapminder like to refer to that as the score a chimpanzee would get randomly pressing buttons. Most people score below four. Pause for a moment and think about the significance of that. Most people have worse than zero knowledge on the state of the world. In their 2017 study of 12,000 test takers from the fourteen richest countries, respondents averaged 2.2 correct answers, and only 10% scored better than random guessing. A remarkable 15% of test takers got all the questions wrong.

If you took the test above and scored below a four, know that 80% of the test takers did as well as you did (the missing 10% scored the same as random guessing; the test was out of twelve for 2017). These results were stable across education levels, incomes, and professions.

Here, we have a collective delusion regarding the state of the world that does not seem to be beneficial like the concept of currency. Like money, however, it does seem to go unnoticed, there doesn’t seem to be a “the world is improving” vs. “the world is in decline” camp. People have opinions on climate change because there is a public debate; we are asked to think critically about the inputs of science, media, and politicians and form an opinion. There are very few debates—and very few incentives—to promoting a worldview of human progress. Whether it is a newspaper or a nonprofit, urgency and tragedy capture attention and dollars better than slow and steady progress.

Who’s at fault? Everyone and no one. Humans have deeply ingrained thinking patterns that lead us toward focusing on stories. We overweight negative information and believe that the availability of information correlates to the veracity of it.

We see patterns where there are none; we look for simple cause and effect relationships; we take shortcuts thinking about large numbers. Consider these factually equivalent headlines:

- “600 million people still live in extreme poverty every day”

- “Global extreme poverty rate drops to historic low of 8%”

- “50 million people lifted out of extreme poverty in the last year”

- “Global extreme poverty rate moves from 8.4% to 7.8%”

While factually equivalent, they all hint at different narratives and some narratives are much better at holding our attention. Media and nonprofits alike will trend toward the first headline. It has a sense of urgency: there is a crisis to be solved and there is suffering. The remaining headlines tell a story of progress. Slow, steady, and some would say boring, progress. Media organizations exist to hold our attention, and evolution has selected us to pay attention to stories of danger and suffering. There was a time when this was a good thing; it kept our species alive in dangerous times. It helped us focus on the most relevant information to our safety. Throughout human history, the more we remember about danger and suffering, the safer we keep ourselves. Unfortunately, these thinking patterns don’t scale well to thinking about the world.

Our brains have also evolved to take thinking shortcuts to save energy. We like to split problems into two groups, which is why we like stories with villains and we love drama. That is why we fear terrorists more than automobiles and sharks more than showering (automobiles and showering cause many more deaths each year than terrorists and sharks do). If we are not careful, we will map all new information into plots that we already know. Unfortunately, slow and steady progress toward solving intricate, complex problems is not that exciting. Yet, as a species, we have been doing just that in a wide variety of domains—infant mortality, famine, extreme poverty, education, human rights, safety—in which we have made huge strides in the last fifty years…to little or no fanfare. In the same time span, media coverage of everything, including those societal ills, has increased.

We are lucky to live in a time where large-scale data collection is possible, increasingly inexpensive, and accessible. We can ask and answer questions about the world, find a public data set out there, and probably someone who has already put it in a graph for you. This strategy allows us to use our thinking capacity to educate ourselves out of this mental trap once we are interested in the question.

EPS has started addressing these narratives, like the one connected to global health, in different places in our academic program. If students can see models for how people have been making a difference in the world, it is easier for them to envision supporting that progress.

It is a good idea to know the status of an issue prior to thinking about how you might make an impact. Most directly, EPS offers two Upper School seminars in this space, Bias: How Humans Fool Themselves, and fittingly, Human Progress in the Modern World. Additionally, we use content from these seminars in our mock classes for prospective students, and I find that progress comes up naturally in a variety of conversations throughout the year with faculty, students, and friends. In each of these settings, we are watching students gravitate to a more accurate delusion, and we hope, shifting their worldviews. Indeed, there are few things more exciting to a teenager than knowing that you have something figured out that 80% of adults do not!

If you are interested in reading more about how humans think, biases, and human progress, check out these resources:

- Factfulness by Hans Rosling

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- gapminder.org

- humanprogress.org

- ourworldindata.org

- callingbull.org