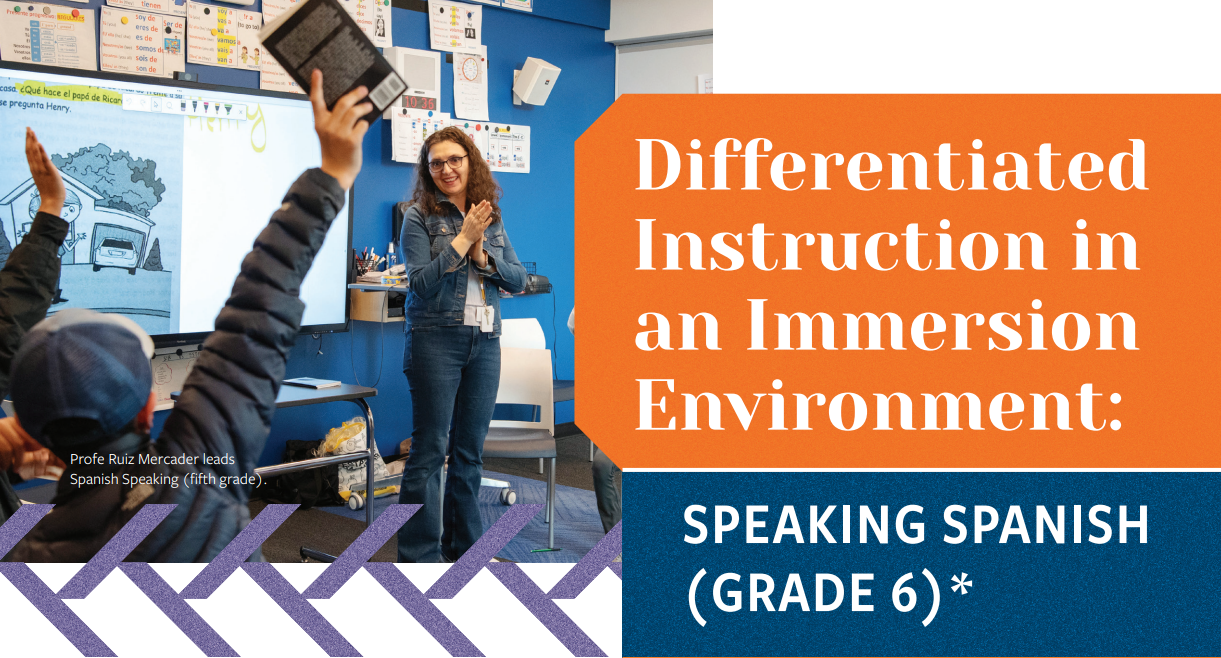

By Dr. Josefa Ruiz Mercader, Spanish Faculty

Neurodiversity is one of the foundational principles of Eastside Prep and is a core part of who we are as an institution. It requires significant levels of differentiated instruction to meet individual needs. Furthermore, when discussing teaching a language, the “spread of the language proficiency levels” is also a variable that directly impacts the diversity of students’ learning needs and abilities within a single classroom.

At EPS, fifth, sixth, and seventh graders take Spanish with their grade mates, regardless of their Spanish proficiency levels. Speaking Spanish (Grade 6) has the greatest range of student learning profiles in the Spanish path of Middle School. To provide some data, in 2023-2024, 20% of the sixth graders had a learning plan and accommodations. In addition, 84% of the incoming sixth graders had never studied the Spanish language before or, if they had, were still “true beginners.” However, the returning sixth graders, after taking Speaking Spanish (Grade 5) at EPS, an immersion program, were ready at the outset to continue learning Spanish in a setting where only Spanish was spoken and heard. This environment can be intimidating for incoming students with low levels of Spanish proficiency, even more so because the curriculum for Speaking Spanish (Grade 6) is also an immersion program.

I use the “Comprehensible Input” (CI) instructional technique to be able to teach using Spanish almost exclusively. Dr. Stephen Krashen introduced this technique, assuming that “you only learn a new language when you understand that language.” I applied CI as a “spiral process.” Students learn the most frequently used words and grammar by starting with just a few words. In the “spiral process,” new words are continuously added. With a lot of repetition, students keep reusing all the words they have been learning from day one to express themselves, often using circumlocution (a roundabout or indirect way of speaking using the Spanish they know). Throughout the years, I have created a “toolbox” of techniques to apply CI to teach in the target language (Spanish). Some of these tools are Quizlet, Gimkit, and Kahoot; inverted classroom; visual support (pictures, videos, acting, and American Sign Language); and storytelling.

In Speaking Spanish (Grade 6), due to the significant differences in the starting points between the incoming and returning students, apart from CI, I also use “Universal Design for Learning” (UDL), which aims to give all students an equal opportunity to succeed. This approach offers flexibility in how students access material, engage with it, and show what they know.

During the 2023-2024 school year, I applied UDL in Speaking Spanish (Grade 6) based on the student needs of this particular cohort in the following manner.

During the fall and winter trimesters, there were two parallel curriculums: the blue curriculum (lower Spanish proficiency) and the green curriculum (higher Spanish proficiency). I used the color of the Seahawks intentionally to explain to students and families that, in the same way that for the Seahawks, green and blue are two fantastic colors to wear, for students, the two curriculums provided excellent opportunities to improve their Spanish proficiency pulling them from where they were. For this to happen, students must select the activities from the blue or green curriculums that better fit their needs for each assignment.

These two parallel curriculums generated three types of moments. There were moments when all students did the same activity, used the same materials, and fulfilled identical requirements (for example, all students played the same “Quizlet Live”). Another type of moment was when all students were doing the same activity (for instance, writing) using the same material (for example, the same picture). However, the requirements were different based on their level of proficiency. The third type of moment was when the kind of activity, the material used, and the requirements were unique for each curriculum.

How did the third type of moment work if all students were in the same space and with only one teacher? Let’s explore an example from a particular day. The unit was “La competencia de fútbol” from the book “La Familia de Federico Rico.” All students had to master the vocabulary of the chapter. However, the learning objectives were different. The blue curriculum focused on learning the body parts and the grammatical structure for possession: “Kylo’s ears (Las orejas de Kylo).” These were concepts the students following the green curriculum had mastered already. That day, I started teaching a mini-class only to the students following the blue curriculum to explain the concepts that were new to them while, at the same time, students completing the green curriculum engaged in two different workstations based on their learning objectives. In one workstation, students working in groups had to create a Quizlet unit with professions that were meaningful to them. In the other one, they were individually writing a text on the whiteboard using a picture. Once the mini-class concluded, I checked in with both groups of students about their productions.

Where was the UDL reflected in these practices? Firstly, students were always the ones deciding on the activities and curriculum to grow their Spanish proficiency. We used two parallel curriculums during the fall and winter, and three during the spring. While there was a more evident division between incoming and returning students during fall and winter, in the spring, incoming and returning students spread over the three curriculums based on each student’s learning evolution throughout the school year. Also, as another way to support neurodiversity, students with learning accommodations could write on paper, type in their computers, or make audio recordings to show what they knew. The combinations of mini-classes and workstations provided the opportunity to introduce new concepts for each curriculum separately and provide plenty of practice based on the learning objectives for each group. This was instrumental in reaching each student where they were. In addition, the configuration of the workstations always included multiple means to fit different learners (computer/whiteboard/paper/board games; individual work/group work). Also, when selecting materials, I looked for those that could be meaningful for students—for instance, using a picture of the World Cup when Morocco knocked Spain out of the tournament since the unit, “La competición de fútbol,” is about winning and losing in a soccer game. This particular match was a recurring topic between students and me since I am from Spain!

*HONORING MY DEAREST LATE FRIEND TERESA SANZ, WHOSE LEVEL OF BILINGUALISM STILL KEEPS INSPIRING ME TO SPEAK ONLY SPANISH WITH MY KIDS AND STUDENTS.

Applying UDL to provide the differentiated instruction required by the wide range of student learning profiles of Speaking Spanish (Grade 6) in an immersion environment has been a rich learning experience. I couldn’t have done it without the support of my colleagues at EPS and the formal structures that EPS provides to share our knowledge, many of which happen during Program Development Days. I am grateful to Lisa Frystak for her presentation during an Evolution of Instruction event; as well as to the people who participated in the discussion of the summer book The Shift to Student-Led. Reimagining Classroom Workflows with UDL and Blended Learning. Learning Support, too, is always very helpful in their assistance to students and teachers.